Monday, May. 24, 1976....Time Magazine

A three-ring sawdust devotee since he was a child, TIME Correspondent James Wilde visited the traveling Circus Vargas when it stopped in Burbank, Calif. His report:

It was "cherry pie" time—circus lingo for an emergency. The trucks carrying the big tent had broken down, and by the time they rolled into downtown Burbank, only five hours remained before show time. Members of all 22 acts ran to help out: clowns, barkers, aerialists, animal trainers, tightrope walkers, acrobats, and Colonel Wallace Ross and his elephants ("ninety-thousand pounds of pachyderms"). Local kids were joining in, lured by the promise of free tickets.

Tired Tiger. For three hours, the bizarrely assorted crew sweated and struggled to raise the 17,508 sq. ft. of brilliant orange canvas in time for the evening's performance. All the while, a small, bearded figure zipped frantically through the melee, hauling on ropes, testing wires and worrying about the wind—and about the chance that a bull elephant might turn catastrophically amorous. When the tent was finally up, Impresario Clifford Vargas glanced aloft and declared with satisfaction: "We are the biggest big top in America."

Circus Vargas' big tent, glowing in the night like an amber mountain, is a cheerful atavism, a reminder of a time when Americans huddled happily on benches under canvas, eating cotton candy and peanuts and staring at the marvels occurring in the three rings before them. Now the Ringling Bros, and Barnum & Bailey Circus ("the greatest show on earth") plays only indoor arenas, driven to cover by the extraordinary expense of raising the big top and creating its own city wherever it goes. Only 18 American circuses are still under canvas, and most are little more than carnivals with a tired tiger or two, barnstorming in a few battered trucks. Three other shows are in the same class as Circus Vargas: Clyde Beatty-Cole Bros., Carson-Barnes, and Hoxie Bros. According to Fred D. Pfenning Jr., former president of the Circus Historical Society, Vargas is a traditional circus of outstanding quality, and the "unique thing about it is its perpetual migration across the country."

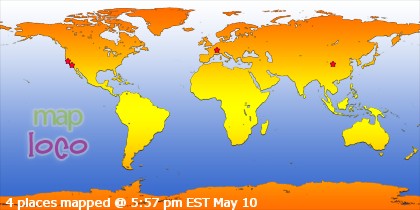

A circus that did not migrate would not be much of a show to Vargas—he crosses the country four times annually, visiting 100 cities and logging 35,000 miles a year. To Vargas, a circus that had no tent would be no circus at all. He spurns the indoor variety as "air-conditioned and sterile. The animals' smell is clouded with disinfectant, and there isn't even sawdust. It's like watching a movie."

From the moment he saw his first big top as a boy, Vargas' obsession was to have one of his own. After marking time as a Fuller Brush salesman and working for the Chicago zoo, in 1972 he bought a small circus that had no tent —a failing he corrected a year later. Says he: "I was starting from virtually nothing, but I knew what I wanted to do."

Doing it seems to require the logistical genius of a Hannibal, the showmanship of a Hurok and the business acumen of a Howard Hughes. A traveling circus has to put up with the whims of the weather, moody animals, occasionally avaricious police and fire departments and frequently finicky bureaucrats who require a sheaf of licenses, clearances and permits.

"There were times when I actually came close to despair," says Vargas, who refuses to give his age because he feels it would bring bad luck. "The worst was in 1974, just outside of New Orleans. It rained for five days and we were floating in an ocean of mud. The high winds collapsed the tent, and it took three days for the elephants to pull out the stakes. Three elephants escaped into a swamp, and most of the trucks broke down. We faced the prospect of being beached forever. I hocked my diamond ring and got enough to get us rolling again. We got back to San Jose and the show clicked. We were on our way up at last."

Now Vargas has 33 trucks, a staff of 160, nine elephants, eight Andalusian horses, a net worth of over $1 million and a debt of about $150,000 that he is steadily reducing by packing in 5,000 people a night, usually in shopping centers. What the customers get for the price of admission ($4.75 for adults, $2.75 for children), is a fast-paced, two-hour show that features some of the best acts in the business.

On the afternoon Vargas shouted "cherry pie" in Burbank, the customers arrived to find a calliope thumping out Thunder and Blazes, a searchlight probing the sky. and an atmosphere redolent of popcorn, frankfurters and musky jungle game. The caged tigers roared, the chimps snarled and the wild, 700-lb. Syrian bears snuffled and muttered about the heat.

Sharp Spikes. The sideshow barkers extolled their wares: "Miss Delilah, the girl who thrives on electricity and smiles when we push the switch on her very own electric chair," and "El Diablo, the king of fire, the human volcano," and "the human blockhead who loves to pound large sharp spikes and razor-tipped awls into his skull."

When the show began, the Great Vashek did dizzying spins on a high wire near the tent's apex. Doris Naughtin smoothly handled the family's motorcycling bears—one of whom had broken her husband's leg just three days before. Pat Anthony turned his eight lions and four tigers into tabbies. The aerial artists performed miracles with no safety net below. When 45 tons of elephants came thundering through the sawdust for the grand finale, the kids could almost reach out and touch their quivering flanks. The pachyderms reared up on their hind legs, unrolled their trunks, and trumpeted farewell.

"Goodbye, girls and boys, goodbye until next year," called out Ringmaster Vargas, resplendent in red tails, white riding breeches, gold-flowered waistcoat and black top hat with a gold band. He looked at the dazed delight on the faces of the children who were walking out. "For a moment," he said, "they have lived in a magic world. I wouldn't sell all this for $10 million."

Sunday, February 22, 2009

The Circus: Escaping into the Past

Labels: .circus., 1976, circus vargas, clifford vargas

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 comments:

Post a Comment